Plea bargains are judicial bribery

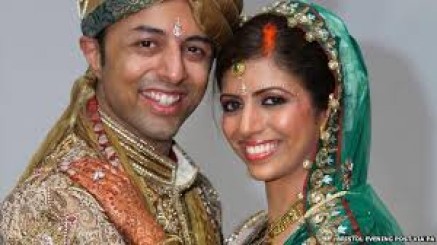

Letepe Maisela, writing in Independent Online, believes SA’s plea-bargaining method may compromise justice in the Shrien Dewani murder trial. In the State’s case against Shrien Dewani, the signs are already there that the prosecution might fail in proving beyond a reasonable doubt that Dewani conspired with the convicted criminals to kill his wife. This is simply due to our judicial system’s over-reliance on the plea bargain doctrine.

At the time, it was thought that our courts suffered serious backlogs and that legislation was required to streamline procedure to deliver justice more swiftly. Legislation was introduced in terms of which provision was made in the Criminal Procedure Act for the formal recognition of a process of plea negotiation, now commonly known as plea bargaining.

To the uninitiated, this is how I think it works. Police arrest the alleged perpetrators. Instead of making further investigations to make their case watertight, they simply persuade one or some of the accused to not only confess to the crime but to implicate the other co-accused as well. The similarity between current criminal investigators and those of the apartheid era is frightening. While the latter simply used torture to extract confessions to nail the kingpin among the accused, our plea-bargaining method simply promises immunity from prosecution or reduction of sentence in exchange for becoming the State witness against what is deemed the big fish they want to nail.

The principle remains the same and it has resulted in police laziness rather than investigative efficiency.

Torture or the promise of indemnity, however, lend themselves to easy dismantling and discrediting by defence counsels. As during most political cases of the apartheid era, where evidence was gathered mostly through torture of both victims and State witnesses, the prosecution often failed to secure a conviction.

This was due to police failure to make a watertight case because of too much reliance on their intimidated witnesses. In most instances, the police even drafted witnesses’ statements themselves.

All the witness had to do was affix their signature and stand in the witness box. Once on their own in the box, they became easy meat for the defence.

Now it would seem that our modern justice has not moved even an inch from that terrible era.

With the embrace of the plea-bargain principle, our judiciary system moved a step backward. Now, instead of using torture, we use something akin to judicial bribery.

In the past, such “co-operation” was called “ratting” or “selling-out”, but today it’s simply called a plea bargain. I will not rule out over-zealous police investigators, like their apartheid counterparts, even “assisting” in the drafting of the statements by the witnesses who have “turned”.

The recent Brett Kebble murder case is an example of how plea bargains can compromise justice. In their desperate attempt to ensnare so-called kingpins Glenn Agliotti and Jackie Selebi, the State allowed self-confessed murderers to walk free. In the end, the State even failed in “getting their main culprit, Agliotti”.

I can now almost see the same scenario playing itself out in the Dewani murder case. The over-reliance on the statements issued by convicted murder accused, who were promised lesser sentences for their co-operation, is already exposing the shoddy manner in which our crime investigators handled the matter.

I sincerely believe our justice system should do away with the plea bargain in its quest to promote efficient crime investigation aimed at successful prosecution. The plea bargain lends itself to abuse by those in power and those in the grip of their power.

To even think murderers, rapists and thieves could tell the truth even against one another is to simply hope against hope.